Section 5.7 Teaching the new courses.

¶Revising topics or trying out new strategies in a single course are ways to initiate reform without much disruption. What this faculty was attempting, however, was changing almost the entire upper level program for majors, both in organization of the curriculum and in instructional approach. During 1997-1998, juniors enrolled in the nine new paradigms courses for the first time while the seniors continued in the traditional curriculum. During 1998-1999, all of the physics majors enrolled in the new courses, both the junior level paradigms courses and the senior level capstones.

Reorganizing the curriculum.

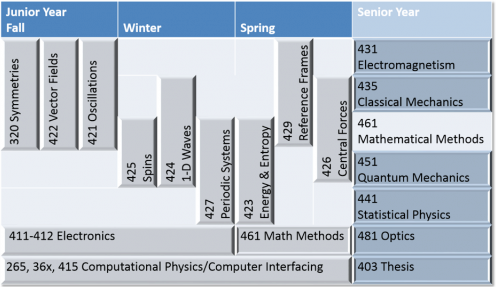

The chart in Figure 2 below represents the current upper level curriculum. The junior year paradigms courses are arranged in the chart to indicate the subject matter preparation they provide for the senior year capstone courses listed in the column on the right.

- Symmetries, Vector Fields, Oscillations, and Reference Frames primarily draw upon topics in Electromagnetism, Classical Mechanics, and Mathematical Methods;

- Spins primarily draws upon Quantum Mechanics and Mathematical Methods;

- One Dimensional Waves and Central Forces primarily draw upon Classical Mechanics, Quantum Mechanics and Mathematical Methods;

- Energy and Entropy and Periodic Systems primarily draw upon Quantum Mechanics, Statistical Physics, and Mathematical Methods.

One of the interviewees was a graduate teaching assistant who described how paradigms courses helped students make connections among mathematical descriptions of similar physical systems:

Well when you take a math course, you learn things that are more abstract and physics is about how do you connect abstract ideas to a concrete reality and so you've learned the mechanics of taking a partial derivative (in math class), but here you can connect it to a physical reality: what does the partial derivative tell me? What is its role in this equation? How does it relate to this physical system?

And by having more than one example, you get more of an intuition about what this object is...I remember I was a TA for a waves course and we did things with light waves that went down a coaxial cable; we did like masses on a string, or masses connected by springs, and so we looked at the similarities between those two equations, the wave equations of those two systems.

Seeing similar equations in different contexts together was important in contrast to her learning experiences as an undergraduate physics major:

I think this is the whole point of the paradigms, that because you look at this equation in more than one system and in more than one textbook, it was much easier for them to grasp the commonalities than it was for me as an undergraduate because in my mechanics class, we didn't talk about, the professor might point out that this equation is a wave equation and it's the same kind of equation as in E&M but it's been a month since I saw that equation in E&M, I'm not thinking about it and I'm not making that connection in the same sturdy way that I do if it's pointed out and it's right there and I'm seeing the comparison.

There also were emotional outcomes from learning in this way:

I saw the undergrads that I TA'd having a really good time, which we did too, but I just thought that there was a lot of energy and fun; there was a lot of fun for the students I think and...they would really come out feeling so kind of pumped up that they could do such a hard thing; they were learning stuff that was so hard and they were like gaining skills so quickly and that just felt really good to them.

The radical reorganization of the content represented by the paradigms courses made possible such comparisons of physical systems and feelings of deeper understanding for the students.

Reforming the instructional approach.

The faculty had agreed to move from straight lectures toward interactive engagement strategies, many of which the faculty “didn't even know about when we started” according to the PI. Current strategies include small group activities, compare and contrast activities, kinesthetic activities, tangible metaphors, computer visualizations, simulations, and animations, integrated laboratories, small white board questions, concept tests (clicker questions), and homework. See descriptions at http://physics.oregonstate.edu/portfolioswiki/strategy:start.

In reflecting upon what she had learned about interactive engagement strategies, the PI commented:

Once you start talking with the students, you start realizing how valuable it is to be getting their input...I think what I learned was that the thing that all active engagement strategies share is that they increase the flow of information from the students to the faculty, that you get a better picture of what it is that is bothering the students and in some cases getting that in the moment in the class and adjusting for what you're hearing and in other cases seeing the patterns of student confusion over years or applying the same idea across courses; just realizing that something is more problematic than we knew it was or learning how wide spread a particular issue is...

An example is the use of white boards of various sizes in multiple ways in class. The faculty learned about using such interactive engagement techniques gradually from many different experiences. Using such techniques can foster positive emotional outcomes for students.

Learning about using small, large, and wall-sized whiteboards. A local high school physics teacher had introduced using small white boards to the university faculty not only through use in his own courses but also during his collaboration in teaching courses at the university. A variety of sizes became prominent in many of the paradigm classes: small white boards for individual student use, large whiteboards for small group work, and whiteboard panels on the walls of the dedicated classroom.

A small white board for each student enables the instructor to ask a question to which each student writes or draws a response. The instructor then can see at a glance what the typical level of understanding is present in this group of students and make an in-the-moment decision about what to say or do next based on that information. The instructor also can pick up several of the small white boards and use these to ground a discussion of the ideas represented by these students' responses. See http://physics.oregonstate.edu/portfolioswiki/swbq:swbq for examples and http://physics.oregonstate.edu/portfolioswiki/whitepapers:narratives:ptchargeshort for a narrative illustrating an instructor's spontaneous use of small white board questions during a class session.

A large whiteboard that lies on the table top enables a small group of students to work together on a problem with their writings and drawings easily visible to one another. A teaching assistant or professor walking by also can see what each small group of students has done so far and decide whether to intervene or not. This is helpful in deciding whether to call the whole group back together for a few moments to address issues that seem to be common to all. See http://physics.oregonstate.edu/portfolioswiki/acts:vfdrawquadrupole for an example.

A whiteboard panel on the wall enables a small group of students to work together on a problem and to present their work to the whole group, with their writings and drawings visible to all. Then the instructor can engage members of the presenting group in a discussion of their work with the rest of the class listening and sometimes contributing to the discussion. This is particularly helpful in what are known as “compare and contrast” activities. See http://physics.oregonstate.edu/portfolioswiki/strategy:contrast:start for an overview and http://physics.oregonstate.edu/portfolioswiki/whitepapers:narratives:lineartranslong) for an example.

Learning about other interactive engagement strategies. Several paradigms faculty visited the physics education research and development group at the University of Minnesota (http://groups.physics.umn.edu/physed/) to talk about their studies of cooperative group problem-solving. In addition, faculty participated in an interdisciplinary OSU project, Making Connections, in which faculty from chemistry, engineering, physics, and mathematics developed activities for a course for at risk students before they started the introductory physics sequence. The PI also reflected upon experiences at AAPT meetings:

I remember the early years of coming home from AAPT meetings with two or three ideas that I'd wonder how that would play out in our classrooms?...I didn't take the activity as a whole but the strategy, or sometimes it was going to Lillian's (McDermott) group's talks and they'd say students are having trouble with this idea and I'd wonder if our students are having trouble with that idea too so sometimes it was ideas and the content and sometimes it was strategies... I picked up these active engagement things one at a time and tried out one thing at a time over many years.

It is important to realize that learning to use interactive engagement strategies can be a gradual process that occurs through many different experiences, both locally and nationally, with colleagues with a similar commitment to talking ‘with’ rather than ‘to’ students.

Positive emotional outcomes of the use of interactive engagement strategies in class. One of the interviewees contrasted experiences as an undergraduate, when she had interactive support only outside of class in the Society for Physics Students (SPS) study room, and the paradigms students' interactive experiences in class:

We had the SPS room, where we would all go to do our homework together, so we were doing homework together, and every once in a while, a professor would stop in or we would see the professor walk by and we'd say, “Hey, we're having trouble with this” and they would come in and talk to us but the students in a paradigms course, they actually get to grapple with things while there's people there to put them back on track, so they don't spend an hour going down a rabbit hole, they still do when they do their homework, but they, like there's a chance to get to do physics with training wheels; it's fun, it gives you this fun experience of succeeding and I think that's a really nice feature..."

The faculty's goal in shifting toward interactive engagement strategies was to increase such positive feelings of success in learning physics in the upper level courses.