Section 3.7 Continuing Engagement of Faculty via Upper Division Committee Meetings

For many years, this physics department had held regular meetings in which faculty teaching lower-division, upper-division, or graduate courses discussed what was happening in their courses and considered ways to enhance student learning. Topics discussed in the Upper-Division Committee meetings varied. A faculty member who had just completed teaching a paradigms in physics course might present to the group changes made and issues addressed. Those teaching a paradigms in physics course before or after this course might comment on the implications of the changes for their own courses or offer insights about the issues noted. Such discussions helped all of the faculty to stay familiar with the content and goals of the various paradigms in physics courses. These ongoing conversations deepened familiarity with and understandings about the connections among the courses, about how each course prepared for and/or built upon the common themes that had guided the faculty during the initial development of the paradigms in physics curriculum.

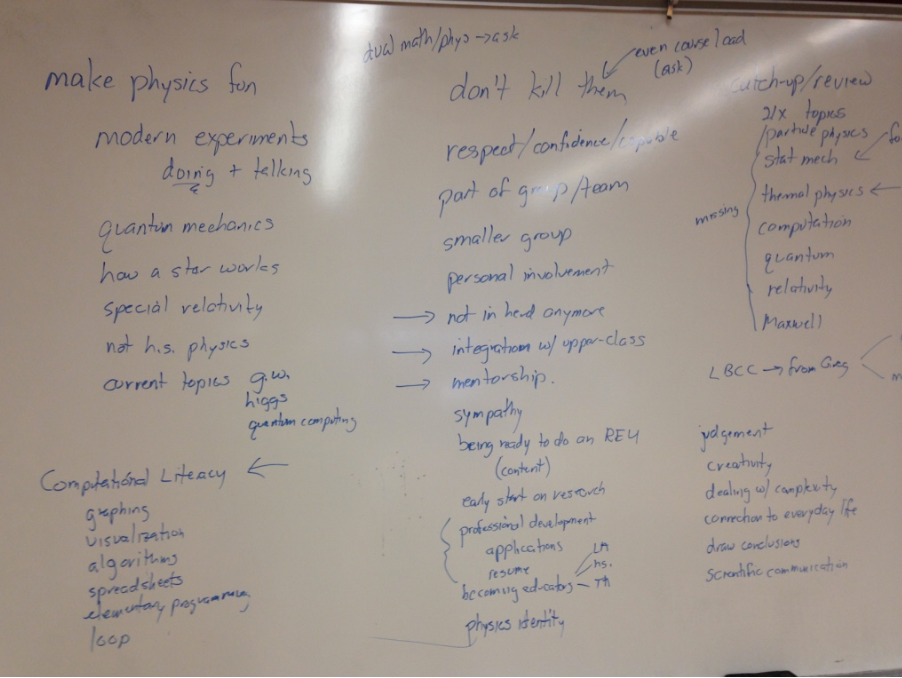

Brainstorming the needs of physics majors.

The upper-division committee meetings occurred during the first, fourth, seventh, and tenth weeks of spring quarter. The second meeting spring term focused upon brainstorming the needs of majors, particularly those still in the lower-division courses. What could the faculty do to ease these students' transition to the upper-division courses, to make this feel less like what an earlier student had described as ‘hitting a brick wall’?

The faculty conference room had a wall-sized white board on which suggestions could be written as offered. As shown in Figure 3.7.1, the conversation started with one faculty member advising “Make physics fun!” What if they offered a new course for majors between the huge introductory physics courses and the junior year paradigms in physics courses, what topics might be the focus? Suggestions included doing and talking about modern experiments, quantum mechanics, special relativity, gravitational waves, the Higgs boson, and/or quantum computing. Another focus suggested was computational literacy, developing skills in graphing, visualization, algorithms, spreadsheets, elementary programming, and looping.

Another thought expressed was “Don't kill them!” noting that the courses for majors needed to be evened out so that the fall term junior year was not such a heavy load, particularly for transfer students. The faculty members present then articulated a variety of aspects of personal issues, that students needed to feel respected, capable, and confident, part of a team, and to develop a physics identity. These students were not in a herd anymore (as in the large introductory physics courses), should be integrated with upper class majors in some way, and get some mentoring, including being ready to get started on research, possibly with an REU (National Science Foundation funded Research Experience for Undergraduates). They needed help in making applications for internships and writing resumes. Some might be interested in becoming teachers.

Next attention turned to the need for these students to review topics from the introductory physics courses or to catch up on topics missing from these courses as currently taught, such as particle physics, statistical mechanics, thermal physics, computation, quantum, relativity, and Maxwell's equations. Aspects mentioned that needed nurturing included creativity, making reasoned judgments, dealing with complexity, making connections to everyday life, drawing conclusions based on analysis of evidence, and communicating scientifically.

As shown in Figure 3.7.2, the group then began articulating aspects of laboratory skills needed. These included being able to produce a full laboratory write-up with purpose, procedure, data, and conclusions, with appropriate attention to uncertainty issues and data analysis, including integration and differentiation from data. The students should be able to create such a document outside of class. Also important was that they be aware of safety issues and have access to modern equipment such as an x-ray spectrometer, microscopes, and photo detectors.

In preparing these students for the paradigms in physics courses, these faculty members suggested developing expertise in solving problems symbolically, including the use of operator quantum formalism, geometric reasoning, and using multiple representations such as interpreting various kinds of graphs. Also important would be building mathematical endurance and strengthening their understanding of functions, including fall-off, circle trigonometry, adding and multiplying graphically, making approximations, using Taylor series and calculus in physics problems.

Starting to design two new sophomore courses.

This meeting of the Upper Division Curriculum Committee created a long list of possible goals for new courses to be offered during the sophomore year. This discussion also provided a collaborative context within which the faculty members most involved in the upper-division courses articulated together aspects of learning physics that they valued. This informed the re-envisioning process for the paradigms in physics courses as well as for possible new courses. During subsequent meetings of the Paradigms 2.0 committee, the members pondered possibilities for two new courses to address at least some of those goals. (See Part VI: Changing Instruction, Chapters 4 and 5.)