Section 4.1 What to teach: Modifying the content.

¶There were some constraints on which courses could be modified. The radical restructuring of the remaining courses began with an early collaboration, proceeded through a long collaborative ‘card-sorting’ process that eventually involved the entire faculty, and culminated in the redesigned Paradigms in Physics curriculum. Construction of content themes specified how various courses addressed particular themes and used common mathematical tools.

Constraints.

In reflecting upon the initial redesign process, the PI noted that in addition to the question of what to teach spring term to accommodate the engineering physics majors' participation in the co-op program, there were some constraints based on other students enrolled in the upper-level courses:

Our optics course and our modern physics course and our electronics courses were all taken by majors from outside of the department so what we chose to do was just address other courses: we had a two-term sequence in E&M (electricity and magnetism), a year-long sequence in classical mechanics, a year-long quantum mechanics sequence, a two-term thermo, and four terms of math methods, which is what I had been teaching for years, so those were the courses that we were choosing to alter.

They also did not include in the redesign several physics electives and a thesis course for seniors.

Early collaboration.

An early form of collaboration had occurred when the PI had begun to use a mathematics computer program called MAPLE:

Probably for the two years prior to this, Maple had just become available for doing visualizations and I had started writing and using some Maple visualizations in the math methods course I was teaching.

A colleague (eventually one of the co-PIs) was teaching the upper-level course on electricity and magnetism and they began to try to coordinate their courses:

That content was really synergistic, so we had made some initial attempts to coordinate how we were teaching the content, so that I would teach something in math right before they needed it for his class...so we were just beginning here to play with both other pedagogical strategies and coordinating content. Up until that time...there was a teaching committee that would tell faculty, in the sense of the course descriptions in the catalog, this content needs to go in these courses, but people were left very much on their own to figure out how to do that.

This is an example of the way that the availability of new technology can open conversation and collaboration among faculty teaching related topics. This early collaboration, however, was limited to only two faculty members attempting to coordinate discussion of related topics in only two separate courses. The redesign of the upper level curriculum eventually involved all of the faculty in reorganizing the content not only for these courses but also for most of the upper-level curriculum as discussed next.

Collaborative card sorting.

An innovative collaborative process evolved for deciding what content to teach and in what order. The PI described this process as follows:

We sat down and tried to figure out how to rearrange the courses to fit these new constraints...What we did was we had people who had been recently teaching courses record the content of their courses on colored index cards...

The colored index cards were green for classical mechanics, blue for electricity and magnetism, orange for thermodynamics, yellow for quantum mechanics, pink for math methods and white for things added in. They first used these colored index cards to consider various ways of rearranging the standard courses:

People who had taught the course recently...made us approximately ten cards per term, often things that were just like the chapter headings in the book. We just got a big table and laid the cards out on the table in the order that they currently were covered and then we rearranged the cards and...so reasonably quickly we found a rearrangement of the terms without very much rearrangement of the content within the courses, so that we could satisfy this need of doing the co-op program.

The department chair offered encouragement to think more broadly:

We took that to...the chair, and he said, “Well, it's really interesting that you have these cards; if you could do anything, not just a minimalist rearrangement, what would you do?”

In thinking about ways to rearrange the content within the courses, they started with an extension of their early collaboration with the electricity and magnetism course (E&M) and mathematics methods course:

First thing...(we) did was we said we'd take the E&M and math methods and mesh them together. So we started just saying, “well these cards would make a nice course and then these others,” so we just started collecting together what we felt would make good courses.

Next they moved the index cards around to bring together concepts that were currently being taught in several different courses. They found that they could sort the cards into six groups with cards of different colors representing similar concepts used in different physics subdisciplines:

We started clustering these things and we got about sixish small courses and then we started seeing a pattern, six small chunks, what would become the paradigms, and that these small chunks typically had multiple colors in them (of the index cards) so we were crossing the traditional physics disciplines. Many were math methods and something else but some were classical and quantum (mechanics); some were E&M and classical; thermo tended to sit off by itself.

Then they began to consider how they could fit these new “chunks” into the curriculum. They formed a tentative plan to offer three 2-credit “paradigm” courses a term for each of the three terms of the junior year. These “paradigm” courses would focus on common themes in multiple subdisciplines:

But once we had these sixish things that would become paradigms, then we stood back and said, “what's happening and how can we fit these into the curriculum that we've always had?” and I think we decided that these were then 2-credit chunks rather than 3-credit chunks and started talking about trying to make nine of them, to fit three per term in the junior year.

Topics that had been taught in the first or second half of the traditional courses seemed to have been treated differently during the card sorting process. This difference suggested focusing content from the second half of the traditional course in each subdiscipline into a capstone course during the senior year:

We also started to notice that these small chunks were from the first half of the year-long sequences so that the second half of a year-long sequence was remaining untouched. And so then we started to say, “ok, let's put the little courses in junior year and the second halves in the senior year” and we started rearranging them to try to fit in, so we could fit the schedule for the co-op students and other things but we tried to fit them in to the spaces that we already had.

Eventually the three PIs sought input from the rest of the faculty by inviting them individually to view the cards in a room where the cards could stay laid out on a table for many weeks:

My memory is that the three of us divided the faculty up by who felt they got along best with whom, and we brought each faculty member up to see the cards. The cards were out on the table for weeks...and we each brought the faculty members up and it was typically one on one, although sometimes it might have been two of us with one faculty member, and we just said to them, “We're thinking about rearranging curriculum in this way, what do you think about this?” And so we really made a point of trying to tap into the accumulated teaching expertise of the entire department, but also we made a point of trying to get buy-in while things were still flexible.

Individual faculty members responded in a variety of ways:

And that was a really interesting process because some people would come up and say, “you can't teach this chunk before that chunk,” but because it was cards, we simply moved them on the table. And sometimes it was we had to add in or take out cards, because somebody would remind us that if you want to teach this, students need to know about this beforehand, so we would be adding cards into an existing course; sometimes it was moving the order of various courses around.

These individual consultations enabled the faculty members to participate in the process with a focus upon their own perspectives:

I would say that a lot of the faculty were really intrigued. And they tended to be intrigued with the potential of a piece of the new curriculum, rather than the whole thing, whatever they had experience with, so they would look at some parts of the cards and just ignore other parts of the cards.

By consulting one-on-one, the PIs provided time and opportunity for individuals to try out their own ideas and to consider the implications of their suggestions:

Sometimes we were able to implement the suggestion that they made and sometimes we weren't. And it was really fascinating when we couldn't; we'd try to do this before that and then you'd see “oh, but then this is coming after that” and we'd sit there and try it sometimes several different ways but the person who made the suggestion would see something terrible happen, and so then they really saw that we tried and they would say, “oh well, the consequences of this suggestion are worst then” and so we got buy-in even when we weren't able to implement.

Thus the card-sorting process provided an extended period in which the members of the physics faculty participated individually in thinking about how to rearrange the content of the courses before the plan was presented to the faculty as a whole for the vote that resulted in adoption of the plan.

Paradigms in Physics Program curriculum.

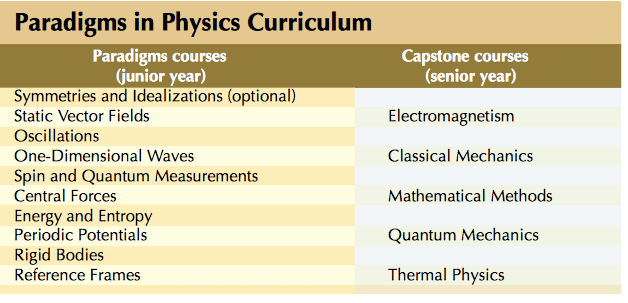

The result was a sequence of paradigms courses in the junior year and a series of capstone courses in the senior year. This radical restructuring was communicated to the physics community in an article entitled “Paradigms in Physics: Restructuring the Upper Level,” published in Physics Today (Manogue & Krane, 2003). The authors summarized the reformed curriculum in Figure 4.1.1 (p. 54):

They explained the new curriculum as follows:

The paradigms curriculum consists of a set of nine intense three-week modules, each an individual course designed to explore themes and concepts, such as periodic potentials, energy and entropy, or central forces, that are common to a variety of fields in physics. Taken in sequence during the students' junior year, the courses transcend the traditional divisions in the advanced curriculum by encouraging students to draw connections between subdisciplines. Each course carries a unique catalog number and students receive a separate grade in each course. In our ten-week academic quarter system, we use the additional week as a preface (to introduce new skills, such as symbolic manipulation techniques) or postscript (to assist students in making the necessary synthesis). The schedule is intense, with courses meeting five days per week in one- and two-hour sessions. (pp. 53-54). During the senior year, students resume a more traditional program, a series of capstone courses in five traditional areas. Because topics from the five areas are scattered through the paradigms, however, the capstones can present a more advanced and synthesized approach to each of the critical areas. (p. 54)

Additional requirements included courses in optics, electronics, a specialty course, and senior thesis.

Content themes.

The design of the paradigm courses emphasized grouping related physical concepts together such as oscillations in classical mechanics, quantum mechanics, electromagnetism, and mathematical physics contexts. However, the PIs also recognized that there were other themes of physics as well as mathematical tools that were common to the courses or developed during the sequence. These included expectation values and probability, resonance, energy, symmetry, normal modes and complete sets of states, and discrete and continuous representations. They constructed content themes that listed when the various courses among the paradigms addressed each theme or tool. For example, understanding of discrete and continuous representations develops throughout the following series of courses:

Ph 421 Oscillations: Fourier series and Fourier integrals

Ph 422: Static Vector Fields: Discrete and continuous charge distributions

Ph 423: Energy and Entropy: Large volume thermodynamic limit

Ph 424 Waves in One Dimension: Wave equation for continuous and beaded string

Ph 425 Quantum Measurement and Spin: Discrete and continuous quantum bases

Ph 426 Central Forces: Quantization as source of discreteness

Ph 427 Periodic Systems: Discrete space

Ph 429 Reference Frames: Individual observers vs family of observers

Appendix A provides a complete version of this list of content themes.